“When you have a program based on minimum standards you get minimum results.” – Darryl Bolke, Hardwired Tactical Shooting

“Private Joker is silly and he's ignorant, but he's got guts, and guts is enough. Now, you ladies carry on!” – GySgt. Hartman, Full Metal Jacket.

I began working toward a relevant defense handgun standard of achievement early in my career as a firearms instructor. One of the most insightful questions I’d ever heard about the ever-popular “qualification” was from Colour Sergeant Clive Shepherd, Royal Marines – after his service to the Crown had ended.

“What exactly are you qualified to do?” he asked.

Excellent point, which he amplified by concluding that the US LE quals he’d seen amounted to “Mickey Mouse accuracy tests.” He’d recommended doing the least possible in terms of quals – if the state requires a certain course fired once a year, do exactly that and no more of the testing thing. Move on to using time and ammo for training, which is a thing altogether different from “qualification.”

But that didn’t answer the question, which is “what is a relevant standard of achievement to be accomplished and documented that would allow us to rest comfortably knowing that you’re carrying a firearm in public?”

That’s a different kettle of fish. I was moved by what I’d seen at the Heckler & Koch International Training Division when I’d spent two weeks with them taking Tactical Pistol and Pistol Instructor. They had a “qualification,” reasonably similar to what I’d seen everywhere else. The also had the Standards, a collection of activities performed by an individual student in front of a particular instructor who’d document the performance. There was an accuracy standard part of each stage, but you had to show, for example, an accurate pair from the holster in a particular time frame. It was pass/fail; you did it or you didn’t.

That’s getting to the point: can I testify as to your skills at a particular time? With the standards, I have only to go to the record. When it’s a line drill, I just know I worked that during that shift, certain people shot a course of fire and each got their scores noted. I can’t testify as to whether a particular person did a particular skill properly for my approval.

I’m not the only one; our own Tactical Professor, Claude Werner, has been working to determine the standards to which we could reasonably hold a concealed carry practitioner. Taking it a step further, Karl Rehn and John Daub have worked through similar efforts to identify how to get training beyond the “1%” – having concluded that one percent or less of those lawfully allowed to carry guns avail themselves of formal training beyond that which is legally mandated.

Among the issues is “lack of interest,” though the time to take a 4-5 day class, along with travel, lodging, ammo costs and the costs of the class often compel people not to try. The number of people with permits (or otherwise lawfully armed) simply seem to “check the box” taking only the legally mandated training -- that’s all it takes to “get the ticket.” (That’s also a problem in civilian law enforcement – too much “checking the box,” not enough “taking care of business.”)

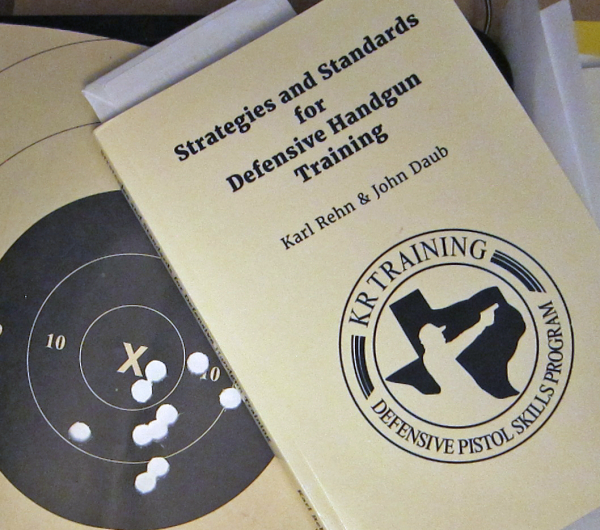

Rehn and Daub’s book, Strategies and Standards for Defensive Handgun Training (Columbia, SC: 2019), documents their examination of the issues involved in getting people to train and figuring out what they should know as they go along.

You’ll notice that, while motor vehicle collisions account for far more death and suffering, few people avail themselves of driver training meant to minimize the chances of such an outcome. Same with first aid and trauma medical training.

Beyond trainee motivations and the popularity of “play” classes, they raise this question: “What do you need, what minimum level of competence does one need to exceed (my addition) to have a reasonable chance of positive outcome in a deadly force event?

Further, what about the legal, medical and psychological aspects post-event?

Those who have untested, unvalidated “confidence” in their skills are afflicted with Dunning-Kruger; these are folks who are ‘safe enough.’ According to the data collected by Claude Werner, there’s something to that in the sense that the violent offenders may be less able than the victim-defenders. That could be a thing called “luck.” Or it could be “guts,” referred to in the quote above.

I’d attended the cash matches in the chat piles near Commerce, Oklahoma after a “novice” win at bullseye and a disaster at PPC during our state peace officers’ convention. I discovered that I hadn’t known what I didn’t know. This was 1980 and a competitor was a watch repairman-jeweler from Berryville Arkansas. His name was Bill Wilson.

I did learn a few things just by watching him shoot. As to learning online, too much of that is, as noted by the authors, “gear-centric,” something ace trainer, peace officer and writer Greg Ellifritz found in his Active Response Training blog. If it was dumping on someone’s (poor) gear selection, it was gold dust. If it was skills drills, the result amounted to chirping crickets.

Going through all this requires listing the problems in finding a relevant standard of achievement for the topic area. As I continue this evaluation – and review of Karl and John’s book – we’ll get a look at the problems to be solved so as to determine the best resolution.

That’ll be next week –

- - Rich Grassi