Editor’s Note: Today’s guest feature, from a couple of years ago in Shooting Wire, was submitted by Greg Moats. It’s very relevant for readers of this service.

As a history major, I found math beyond basic algebra and geometry to be theoretical and perplexing. I saw the utility in understanding a projectile’s ballistic co-efficient and standard deviation readings on a chronograph and I understood that geometry could help determine an angle of deflection or figure a parabolic trajectory. However, differential equations seemed like a mystic dark-art and a waste of intellectual energy. The exception was a business-math class that I took in Probability and Statistics which, while mundane, took on the semblance of practicality although I’ll confess its application went unused in my everyday life. When it came to statistics, “figures lie and liars figure,” was my default position if the statistics didn’t coincide with my beliefs, assumptions and biases. “The facts speak for themselves,” was my default when they did coincide.

Enemies of the second Amendment have found that prefacing a conclusion with a statistic or a statement of probability, even when ridiculously distorted, has a distinct ring of truth. Case in point, Dr. Arthur Kellerman stated that, “a homeowner's gun was 43 times more likely to kill a family member, friend, or acquaintance, than it was used to kill someone in self-defense.”* (Figures lie). On the opposite end of the intellectual spectrum I saw in this morning’s news feed that Tom Arnold (hardly a candidate for president of his local chapter of Mensa) stated that 80% of gun owners shoot themselves or members of their own families!** (Liars figure). Kellerman’s missive of probability and Arnold’s statement of statistics will appeal to the naive, ignorant or stupid, and to be anti-gun requires some combination of the three.

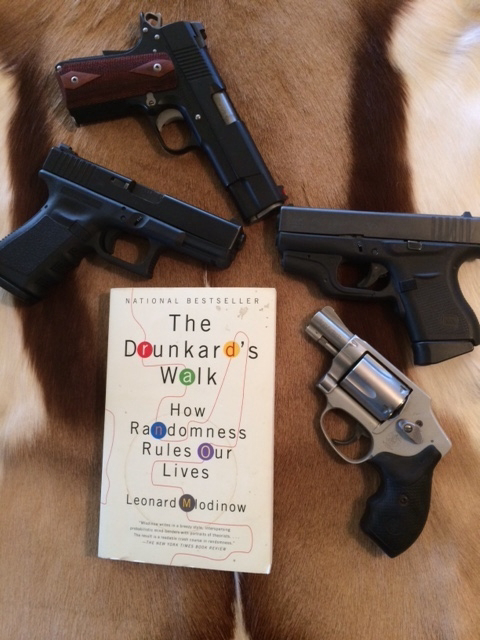

My intent here is not to grind some political axe, but to relate the reading of what I found to be a fascinating non-shooting-oriented book about the mundane subject of probability; The Drunkard’s Walk—How Randomness Rules Our Lives, by Leonard Mlodinow.

The proliferation of concealed carry prompted my re-interest in probability some 36 years after my mundane college course. As I considered what I “needed” to carry, I had to come to terms with the statistical probability of its use. How much “stopping power” did I need? Did I need a .45 or would a 9mm suffice? How much ammo was “enough” to carry and in what capacity (i.e. a large capacity double-stack or a single stack with multiple spare magazines)? What was the probability that I would ever use and therefore needed to carry a handgun at all? Questions like these caused me to search for some statistical underpinnings for my assumptions. Spoiler alert: the book doesn’t answer those questions, but it does cause thinking “outside the box.”

All persons concerned with self-defense have to sift through the abundance of patterns that clutter the nature of their everyday lives. The challenge is determining which of those patterns really matter. “I’d rather be lucky than good,” is a sarcastic aphorism occasionally heard in feigned attempts at humility.

“Luck” is defined as “chance considered as a force that causes good or bad things to happen.” “Chance” is defined as “the occurrence and development of events in the absence of any obvious design.” “Obvious design” in nature takes the form of patterns and frequencies.

If a specific voting precinct -- let’s say in Florida for example -- casts votes in excess of their total recorded population for three elections in a row, that constitutes a frequency that points to an “obvious design.”

Cooper’s color-code becomes significant when identifying patterns and frequencies. The key, according to Mlodinow is to avoid excess or deficiency. For example Cooper’s color-code presents a spectrum of “Alertness” (conditions Yellow, Orange and Red) and “Inattentiveness” (condition White). Excess alertness becomes paranoia, excess inattentiveness becomes stupor just as excess courage leads to recklessness and excess timidity becomes cowardice. Aristotle called this area between excess and deficiency the “Golden Mean.”

“Frequency” is a two edged sword. Events don’t occur, until they do. The fact that something has never or seldom occurred doesn’t mean that it won’t occur in the future. Just because you’ve never needed to shoot someone in the past doesn’t mean you won’t in the future just as 100% of last year’s murder victims had never been killed before. On the other hand, frequency is usually the safe bet depending on the severity of the wager.

In firearms training circles we constantly see people over preparing for low frequency events and neglecting higher frequency events. Take for example the current popularity of Long Range Precision Rifle courses. As the former OIC of a Battalion Scout/Sniper squad, I completely understand the allure of understanding the Coriolis Effect and value the ability to place rounds on targets in excess of 1000 yards. However the average law enforcement sniper shot is 51 yards (yes, I know, figures lie and liars figure, but those are the statistics readily available so “the facts speak for themselves”). For a retired civilian like myself with no credentialed “sheep dog” responsibility, long range precision shooting requires a skill set of such low frequency as to be statistically non-existent.

In the same vein, take the example of carrying a spare magazine and refining the skills of the speed reload. I don’t doubt that somewhere in history, a civilian has been engaged in a fire-fight that expended enough ammunition that a speed reload was required. I just can find no documented case of one. (If you have documentation of such an occurrence, please let me know via the Outdoor Wire Digital Network). At any rate, it would be an extremely low-frequency event. On the other hand, there have been countless occurrences of magazines that have shot craps in the middle of shooting events be they competitive or combative. Therefore the probability of needing a speed reload due to equipment malfunction is high compared to the same need caused by ammunition expenditure. Probability-wise therefore, carrying a 17 round sidearm with no spare magazine is less prudent than carrying a 7 round sidearm with a spare magazine. You may be able to shoot holes in my logic, but it works for me.

My friend and master-trainer Dave Spaulding has the habit of asking his students why they use the equipment and techniques that they do. It’s one of his endearing talents that helps lead students to clarity of thought. Mlodinow’s book, The Drunkard’s Walk—How Randomness Rules Our Lives, may help you achieve similar results.

Notes:

*https://guncite.com/gun_control_gcdgaga.html

Greg Moats was one of the original IPSC Section Coordinators appointed by Jeff Cooper shortly after its inception at the Columbia Conference. In the early 1980’s, he worked briefly for Bianchi Gunleather and wrote for American Handgunner and Guns. He served as a reserve police officer in a firearms training role and was a Marine Corps Infantry Officer in the mid-1970’s. He claims neither snake-eater nor Serpico status but is a self-proclaimed “training junkie.”