I wish I could say I remembered each stage of the first law enforcement handgun qualification I ever shot; I can’t.

I had to rely on a digital image from a newspaper clipping from that first year of my service, 1977. It related – remember this is from a newspaper story – a description of the course fired. It started, the story says, with twelve rounds from the hip, including draw and reload, in 30 seconds at two yards. This is alleged to have been followed by the same thing at seven yards, done twice. The story doesn’t explain that this was from a so-called “point shoulder” position, the gun at more-or-less eye-level but not “aiming.”

Now that’s called ‘target focus’ or some variation thereof. From fifteen yards, it’s the same time, same drill, but “he is allowed to aim the weapon at eye level.”

A total of 48 rounds or so it appears, with 70 percent to pass.

I recall no instructions before the qual attempt. I do recall that we shot at 25 yards – perhaps six rounds or twelve, cutting the second, superfluous string from seven yards.

Never believe the press.

As to the point of successive cylinder dumps (I used a Colt National Match 45 – pre-Gold Cup), I think that was to provide practice at reloading the gun. The point of ‘unaimed fire?’

Maybe it was the proximity or it was “you won’t be able to see your sights.” In those days with some of the elderly hardware being carried, that could well have been it.

After a few years in service, I referred to the “qualification” courses as endurance contests. No one could tell me just exactly what we had “qualified” to do. Still, the handgun manipulation during this event was more gun handling than most of our people would do for the rest of the year. It wasn’t nothing.

At basic, the course – I believe, going from memory – extended to more-or-less the NRA Service Revolver event, with some additional rounds to bump it from forty-eight to sixty rounds of ammo. That requires more endurance, more focus over a longer period.

And we definitely shot from 25 yards – quite a bit.

Shooting handguns accurately isn’t easy. Not particularly complex, but not easily accomplished.

We had a classmate in basic that had gone from a nonsworn clerk position to an investigator position in her department – likely the only way to get her a well-deserved pay raise. The wise instructors recognized that that two-inch snub she actually carried was tougher to shoot than a then-standard four-inch gun carried by uniformed personnel. Arrangements were made for her to get a loaner service gun.

Because why actually prove competency with a gun you’ll actually carry, right?

I had no idea how police handgun training had gotten to this point. I was aware of speed loaders (couldn’t use them in the academy as they gave an unfair advantage over shooters who didn’t have them); I was aware of Jeff Cooper and the only real service sidearm, the modern heavy-duty semiautomatic pistol. I knew to aim the handgun when shooting it.

Still, I’d gotten a Smith & Wesson Model 66-1 so I’d fit in.

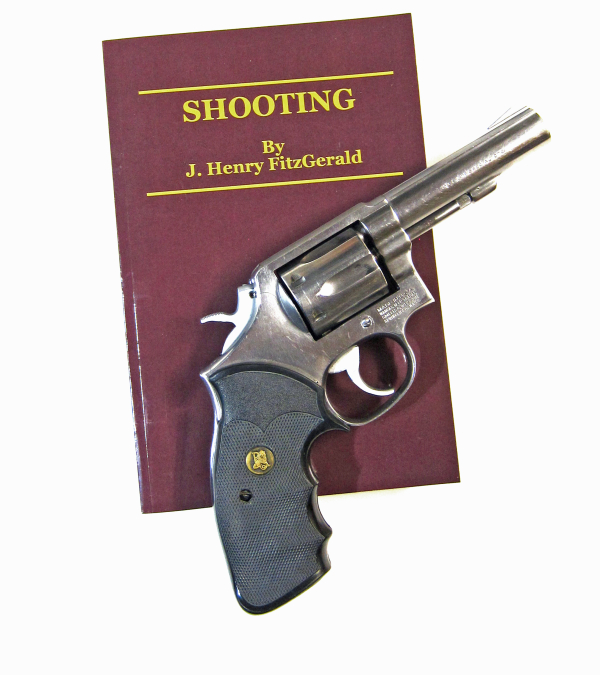

It wasn’t always that way. If you go back to a book written by John Henry Fitzgerald, he specifies what became the B-21 target (an analog of which we used in Basic). His course combines times to accomplish the task plus score on the target. It started with experiential “warm-up,” untimed for six rounds at ten yards, three right-handed, three left-handed. The course used a pair of targets for each shooter; the left target was for left-handed work. He had right- and left-handed strings throughout the course, emphasizing the nature of the “handgun,” not the “hands-gun.”

There was movement to firing positions with gun in hand – something that would give range officers of my early career a bit of anxiety. The course also required close range “high percentage” shots to a smaller preferred target area.

From that, we went to something different.

The FBI course from the 1940s was an early course that required drawing from a holster, shooting from various positions, reloading under time pressure, movement and rapid fire at closer ranges. Drawing and shooting from sixty yards in, doing sequential cylinder dumps – five rounds in those days, to become six-round dumps later. They moved from “five-reload-five” to “six-reload-six.” Conceivably if they were still organizing revolver training for police today, it’d be “seven-reload-seven” – for the S&W M686+ or the Ruger GP100.

It seems that the more-or-less standard police-NRA-FBI quals taken from match shooting – qual courses took on the characteristics of police revolver competition. The question is does the match course of fire relate to occupational necessities?

We started moving back to the shorter-string shooting, some engaging pairs of targets on a spotty basis, as you can find in the literature that’s been uncovered and displayed in the KR Training blog posts. One of the movers on this front was John Dean (Jeff) Cooper – but there were others nibblin’ around the edges at the same time. The greatest impact was that of Jeff Cooper and that was because of his excellent communication skills, starting alternative match competitions and opening the American Pistol Institute – Gunsite.

Still, much of this centered around building individual skills – and assessing staff on their ability to perform these tasks on ranges. There has to be something beyond that.

If you want to do the sequential mag-or-cylinder dumps punctuated by reloads -- and you think that’s the key to good training, practice and skills assessment – well, bless your heart.

— Rich Grassi