Editor’s Note: Today’s guest feature is from our contributor Greg Moats.

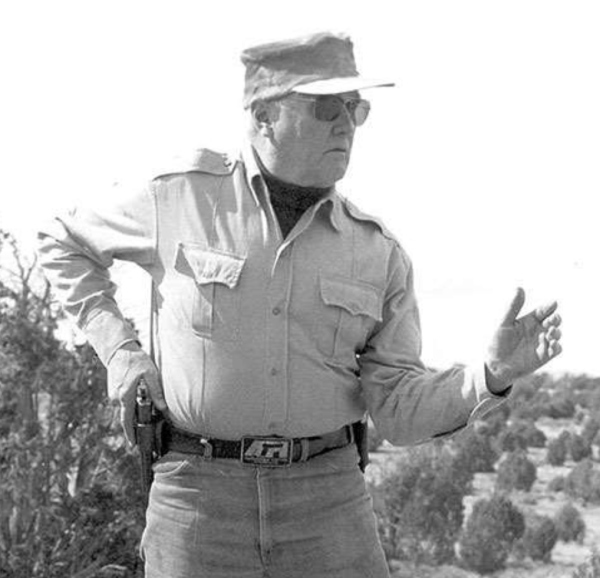

The last half of the 1970’s was an exciting time to be a pistol enthusiast. Jeff Cooper moved to Arizona and opened the American Pistol Institute (now Gunsite Academy), IPSC was formed at the Columbia conference, a new periodical (American Handgunner) dedicated to our interests hit the newsstand, new forms of competitive shooting (“Practical” shooting, the Bianchi Cup, the Second Chance bowling pin shoot) blossomed. Also pistol smiths like Jim Hoag, Armand Swenson and Pachmayr produced refinements to the 1911 platform which, while avant-garde at the time, are de rigueur on many of today’s factory production guns. During this same time, Elmer, Skeeter and Bill (Jordan) were no less popular nor less influential, however Cooper kick-started pistol craft and took it in an almost entirely new direction. Some of us young pups grabbed a hold of the tail of the comet and went along for the ride! Those of us lucky enough to be in the right place at the right time got to work with Cooper and came to realize that he had more disciples than friends, and he seemed to like it that way. Whatever we were to him, to us he was (and remains to this day) a hero.

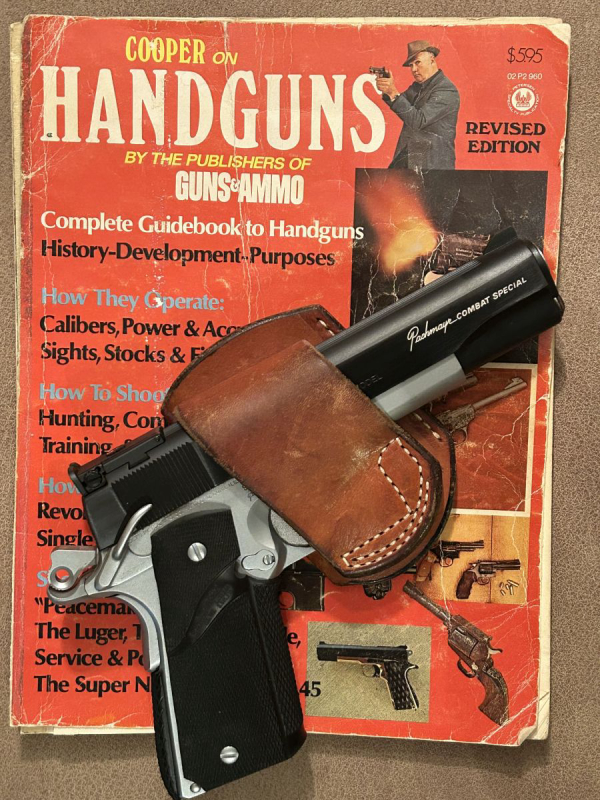

Many of the heroes of the shooting world are irrevocably linked to specific items, but few more notably than Jeff Cooper and the Yaqui Slide holster. In 1974, I was a senior in college about to graduate and ship out to Quantico when “Cooper on Handguns” was published. On page 98 I saw my first Yaqui Slide and read Cooper’s description and explanation:

“A couple of years ago, Eduardo Chahin of San Salvador showed me a particularly well-designed version of what has long been called a Yaqui-slide—a sort of superior belt loop which carries the pistol comfortably and unostentatiously over the right hip … It is friction-tight against two Gs, while still as fast as any other waistband carrier. What is most outstanding about it is that you can just leave it on your belt when you take off your pistol. It does not look like a holster, and, without a gun, it attracts no attention even when worn with no coat … A very similar product is available from Milt Sparks of Idaho. The design is not as simple as it looks, however, and it costs as much to make as a full holster.”

During the next few years as IPSC and the American Pistol Institute gained increasing notoriety, pictures of Cooper conducting range sessions while wearing his Yaqui Slide seemed to pop up everywhere. The holster became wildly popular, as much I think, for its appearance as its function. Tony Kanaley who ran and subsequently owned Milt Sparks Holsters after Milt’s passing in 1995 said that Cooper approached Milt about manufacturing the Yaqui here in America and Milt subsequently paid Eduardo Chahin a royalty for years for the use of the design.

Red Nichols, my old friend from my days working at Bianchi, states that the Yaqui Slide is not technically a Slide holster. According to Red a Slide holster is an “abbreviated pancake holster;” basically two flat pieces of leather with stitching forming a pocket for the handgun. In the pre-IPSC days, I purchased a Slide holster manufactured by Don Hume. It sat very close to the body making it superb for concealed carry and the stitching of the two flat surfaces at the front of the handgun pocket formed a sort of channel for the front sight. If you fed your belt through a pants belt loop in between the two belt slots cut in the slide, it could never get too loose, but you could conversely tighten your belt to the point that the gun was un-drawable. By contrast, the Yaqui Slide is described by Nichols as “a folded holster sewn to a folded belt loop,” hence Cooper’s comment, “The design is not as simple as it looks.”

As an historical footnote, after its inception in 1976, IPSC quickly became enmeshed in the “Gamesmen vs. Martial Artist” controversy. The Gamesmen won. During the first National Match conducted in Colorado in 1977, a few competitors wore Yaqui Slides and gun writer Rick Miller and IPSC VP Dick Thomas even competed wearing Cooper/Hardy shoulder holsters; very much a Martial Artist atmosphere! By the 1979 Nationals things had changed and the three most popular holsters worn were Spark’s “Hackathorn Special,” Gordon Davis’ “Usher International,” and Bianchi’s “Chapman Hi-ride” -- for this tournament almost all were worn in the cross-draw position because one of the events was the “Cooper Assault Course” which mandated a weak hand draw from the kneeling position requiring contortionist flexibility to accomplish with a strong side holster. The popularity of the Yaqui Slide had been eclipsed by holsters such as those just mentioned.

At that same 1979 IPSC National match, I won a Yaqui Slide donated by Milt Sparks and stamped on the back, “I.P.S.C. NATLS. 1979.” In the subsequent 45 years, I’ve treasured the holster, worn it frequently for social carry and even occasionally for competition-carry. I’ve concluded that it’s not an imperative piece of gear that every serious hand gunner HAS to own, but every serious hand gunner with a sense of history and tradition SHOULD own one.

The Yaqui Slide is not without some drawbacks and its critics are numerous and uninhibited about voicing their contention.

First, the design does little to protect the handgun as only about 1 1/2” of the pistol is covered by leather. This may be a major concern if your daily activities include crawling on gravel, bulldogging steers or riding unbuckled inside an M1 Abrams tank. However, if it’s worn under a concealing garment or used mainly as a range holster, that argument seems trivial.

A more noteworthy objection to the Yaqui Slide was voiced by Tony Kanaley when asked why he discontinued the product while running Milt Sparks Holsters. He mentioned that the reason had “to do with the holster being more suited to the old school, ramped front sights that no one seems to have use for anymore. During a draw, patridge or sharply serrated, semi ramped sights, can hang up on the bottom of the original Yaqui Slide, thus causing the gun to be ripped out of the hand and go pinwheeling across the living room floor.” Additionally, an un-ramped front sight can tear up the bottom of the front loop on the holster.

There is a major nuisance that the holster causes -- one must learn to “corkscrew” themselves into an armchair to prevent the muzzle of the pistol from being pushed up by the arms of the chair. The first time that I wore my Yaqui Slide in public was to a movie theater. I sat down and left the butt of my pistol rub about 2” below my armpit. My cover garment kept the handgun from tumbling out on the floor and the lights had been turned off so I was able to recover the gun safely without having the auditorium evacuated. The only people that carefully consider the width of the arms of a chair prior to sitting down are the morbidly obese -- and those wearing a Yaqui Slide. I can attest to both empirically.

There’s one final issue with the Yaqui Slide that I stumbled across five years ago. Jerry Mickulek conducted a shooting class here at my range in Wyoming. Jerry teaches drawing the pistol by making contact with the gun from the side and wrapping more of your hand around the front of the grip than virtually all other trainers teach students to do. To accomplish this, the dominant arm needs to bring the elbow outboard instead of straight back, a technique typically called “chicken winging.” With a kydex range holster, the maneuver felt foreign but “snag free.” A day or two after the class, I practiced the same technique with a Yaqui Slide and was unable to complete the draw stroke at all! By shifting my elbow outboard, it caused me to twist the handgun while lifting it upward. Once the trigger guard clears the holster, the gun is free to turn inboard while still in the loop of the slide and becomes like pulling a square peg through a round hole. I stepped away from the wall and consciously moved my elbow directly to the rear (and parallel to the holster) during the drawing stroke and it went fine. The Yaqui Slide holster demands that the elbow move straight to the rear to insure a flawless draw.

The design may not be perfect but it’s given good service over the years. My friend Sheriff Jim Wilson has used one frequently and thinks highly of them as do a number of other pistoleros and a substantial percentage of Gunsite instructors and graduates.

Unfortunately, neither Eduardo Chahin nor Milt Sparks had the name “Yaqui Slide” registered as a trademark. As a result, almost any holster cut such that a portion of the barrel sticks out the bottom is referred to as a Yaqui Slide. The only current holster company that I’m familiar with that is making a true Yaqui Slide is Barranti Leather, one of the premier leather smiths in the business. On their website, they credit their holster as their “version of the holster built by the late Milt Sparks.”

When I look at my treasured ’79 holster, I feel that spark of fervor that I felt the first time that I read “Cooper on Handguns” and the excitement felt in the early days of IPSC. It’s not the best holster design in the world, but every history fan should own one.

Just because.

— Greg Moats

Greg Moats was one of the original IPSC Section Coordinators appointed by Jeff Cooper shortly after its inception at the Columbia Conference. In the early 1980’s, he worked briefly for Bianchi Gunleather and wrote for American Handgunner and Guns. He served as a reserve police officer in a firearms training role and was a Marine Corps Infantry Officer in the mid-1970’s. He claims neither snake-eater nor Serpico status but is a self-proclaimed “training junkie.”