Today’s feature is from correspondent Dave Spaulding

I recently read a posting on the internet that caused me to scratch my head. The author made an impassioned plea for the superiority of the .45 ACP cartridge over all others claiming, “ball .45 will stop a man 9 out of 10 times with a well-placed hit.” He based his assertion on testing that took place 100 years ago. It was quite clear the author was not stating fact but was trying to shape other’s thoughts based on his opinion. Alarmingly, less informed individuals were thanking this writer for his “timely information.” The sad thing is people were accepting his words as gospel for no other reason than they read them on the internet.

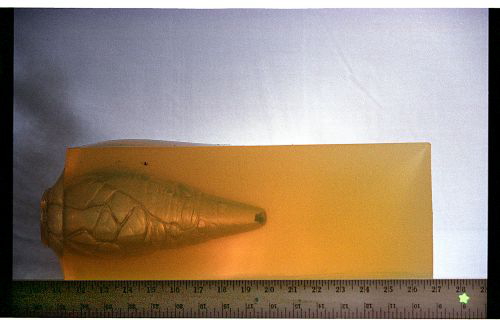

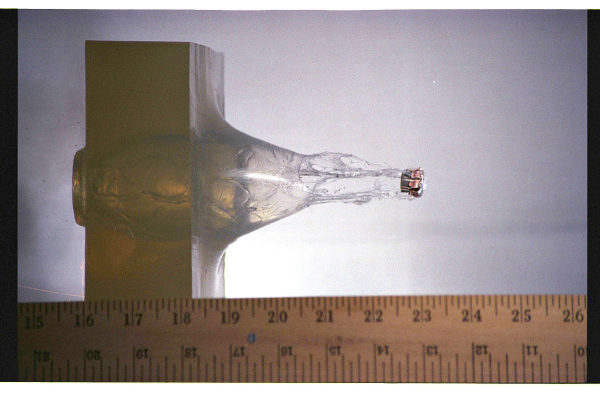

For many years I was deeply involved in the stopping power debate. I read everything I could, talked with trauma surgeons, coroner investigators, medical examiners and even collected my own shooting reports. In 1987 I wrote my Master’s Thesis on the topic entitled The Incapacitation Effectiveness of Police Handgun Ammunition and based my conclusions on shooting data that was supplied by law enforcement agencies across the country. My agency allowed me to use agency letterhead to reach out and solicit shooting reports and I was very pleased at the response I received. By the time I finished, I had a kitchen table stacked with shooting/autopsy reports from all over the United States with so much data I could hardly process it. One thing did stand out, however: for every shooting in which a particular caliber and bullet style performed well I also received one in which it failed. In truth, I could not really draw a conclusion based on the shooting data I received. I decided to bolster my thesis by testing popular police ammunition in duct sealant, water soaked “undertaker’s” cotton and ballistic gelatin as all three were commonly used in the gun magazines of the time. The three test mediums resulted in different performance which I should not have surprised me thinking back, considering the three mediums were really nothing alike.

Upon its release in 1987, I became fascinated with the FBI’s Wound Ballistic Panel report, a group that was formed after the tragic April 1986 shootout involving a team of FBI Agents and two hard core robbery suspects in Miami, Florida. While the robbers were killed during the confrontation, so were several FBI Agents and an extensive study resulted with ballistic experts from across the country being brought together to try and determine what went wrong and what could be done to ensure such a tragedy never happened again. It was determined the FBI’s issue 9mm load, the Winchester 115 grain Silvertip hollow point, did not have sufficient penetration power and that a bullet that could push deeper, especially when shooting through other objects to get into the torso, would be the right formula. I poured over this report when it was issued as it made so much sense and I lobbied my agency HARD to get them to adopt the new Winchester 147 grain OSM hollow point, even though law enforcement had received good performance from the 115 grain Silvertip in recent shootings. Interestingly, a friend of mine, who served in the intelligence community, told me they were very pleased with the Silvertip. He advised they had issued it to several protection teams they had trained across Africa and it performed very well in a number of shootings. He advised they were a bit perplexed by the FBI’s stance at the time. But science was science and could not be disputed, until it was proved to be wrong.

As it turned out, my former agency had one of the first shootings in the nation with the Winchester 147 grain OSM load and it failed miserably in a scenario that would seem to be perfect for its “enhanced” penetration capability. One of our deputies responded to a report of a child kidnapping. Our deputy was able to stop and confront the kidnapper in a parking lot. The deputy was about ten feet from the suspect when he engaged him, pointing his Smith & Wesson Model 669 semi-auto through the open passenger window of the suspect’s vehicle. The child was sitting in the passenger seat while the suspect sat in the driver’s seat with his hands on the steering wheel. When the suspect tried to flee, the deputy fired one round of Winchester 147 OSM grain hollow point ammo at him, hitting him in the right arm which blocked the bullet’s path to his chest cavity. This should have been no problem as this was a penetrating round, so it should have passed through the arm and entered the suspect’s chest much like the Miami scenario. Too bad it did nothing of the kind. It stuck in the suspect’s elbow allowing him to flee, resulting in a high-speed chase involving multiple agencies and several crashed cars.

“But the ballistic gelatin said ...”

Once the suspect was in custody, he was taken to the hospital where it was determined the bullet did not do sufficient damage to warrant removal. To the best of my knowledge, this suspect still has the bullet in his arm to this day. The remaining rounds in the gun were chronographed at the crime lab from the 669 and determined to have an average velocity of 630 feet per second. The ammo that I lobbied for was immediately removed from service and the Silvertip load was re-issued at a substantial cost to the department. It took a long time for me to recover any credibility and I became an outspoken critic of the 147-grain load. Is it hard to understand why? Noted trainer and writer Massad Ayoob took this story and retold it whenever the subject of the 147 grain 9mm was brought up.

To be fair, the current generation 147 grain 9mm loads have proven to be quite good with the Federal 147 grain HST leading the pack. I carry the 147 HST in my EDC Glock 19 as I have been quite impressed with the actual street results of this load. In addition, it (and its American Eagle training equivalent) has shown to be exceptionally accurate and I like to shoot 3 x 5 index cards at 25 yards. That said, I consider ballistic gelatin tests to be an indicator of potential performance and not what a bullet will do once it enters the human body. I believe history has shown this to be the correct viewpoint. It should be noted that over the last few decades, we have had enough shootings to be able to correlate tissue with gelatin for a higher level of accurate prediction.

In this “apples to apples” testing environment one will note the best .45 bullet will create a 15 to 18 percent larger wound cavity than the best 9mm. This is certainly encouraging and would lead one to believe a bigger bullet is a better bullet -- I think that would be a fair statement. Now for the harsh reality: that 15 to 18 percent is measured in millimeters meaning it is not enough to make up for poor shot placement. To stop someone with a handgun bullet you need to either hit an important organ (brain, spinal column, aorta, heart, etc.) or create rapid blood loss by severing a major artery and any of the commonly used law enforcement/defense rounds, regardless of caliber, will do this. It might take multiple hits, likely some would say, as a drugged or determined adversary can be tough to stop quickly with any small arm.

In my classes I have a drill each student shoots to see if the gun/caliber they carry is compatible with their level of skill. I call it the “Two Second Drill” and it is merely four rounds fired at twenty feet into a 6 x 9-inch rectangle. This represents the high chest region where many vital organs are located, twenty feet is the length of a typical confrontational distance and four rounds fired in two seconds is a reasonable time limit based on the history of armed conflict. Broken down, the drill is the first-round hits in one second from a ready/muzzle diversion position with the final three spread over an additional second or in splits of .33 seconds. To me, this shows the student can control the recoil of their chosen pistol and caliber. It is amazing how many people cannot accomplish this simple drill because they are shooting “too much gun” for their individual skill level.

These days I pay little attention to the stopping power debate unless I happen to stumble across something really stupid like I did above. While confidence in a particular gun and caliber is important, it is more important that you be able to control the gun/caliber in accurate reasonably rapid fire as multiple, accurate shots will be what likely ends a pistol fight. Oh yeah, and you might have to do this while moving rapidly, not merely taking a single sidestep. After all these years, I have come to understand that the secret to handgun stopping power is where you shoot your adversary and how many times you can shoot them. This requires training, practice; skill and a level of ruthlessness that permits you to stand up and exchange potentially life ending rounds with another human being. Some old west gunfighters called it “deliberation” a word I am trying to bring back when combative pistol craft is discussed. No amount of new gear or “wonder” gun will change this. In the end, what will a person be doing after you shoot them? Probably the same thing they were doing before you shot them, a harsh reality indeed.

-- Dave Spaulding